The interesting analogy between language and biology

On the interesting parallels of language and biology: a taster

There are interesting parallels between language and biology. As a result, problems surfacing in natural language processing (NLP) tasks, may well inform us about possible problems and solutions in computational biology.

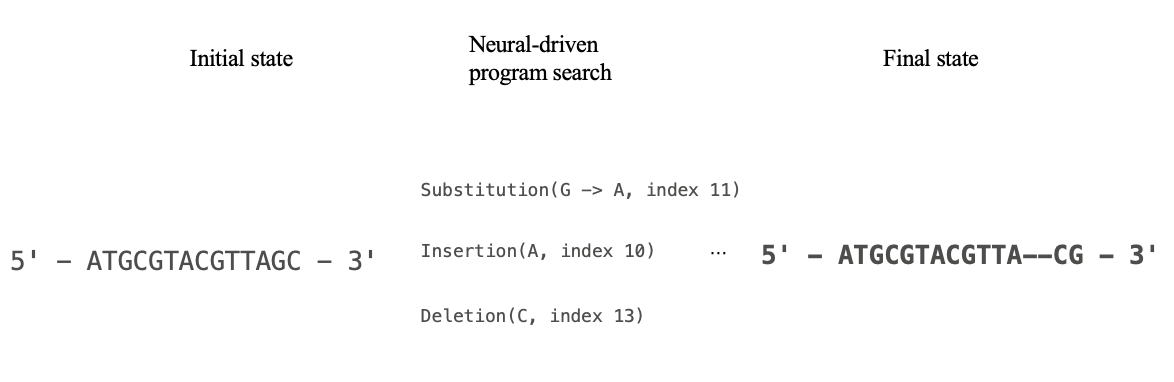

The simplest common denominator to observe the parallels concerns the analysis of sequences: algorithms and modelling paradigms like recurrent neural networks and self-attention in transformer that help process a sequence of words to solve a task like text classification can surprisingly work with sequences of genes to classify what disease does an RNA sequence correspond to. This is because at a computational level, a string of nucleotides (adenine (A), thymine (T) or uracil (U) in RNA, cytosine (C), and guanine (G)) can be represented as a sequence of letters.

Another common point concerns the representation of words and biological entities. It would not suffice to represent a word like ‘airplane’ based solely on this string (i.e. this symbol) so it is common to use a fixed-size embedding vector to denote it. This be extracted from open-source libraries like GLoVE and word2Vec. In parallel, molecules also have expert-coded or learnt molecular fingerprints as vector embeddings which are readily available in RDKit. Another case is that of obtaining embeddings for biological entities. A gene can be treated as a vocabulary token, while a cell can be treated as a sentence. Another work on a similar vein is Cell2Sentence, where gene expression (single-cell transcriptomics) is treated as text.

Language-agnostic grammar: structure for language and biology

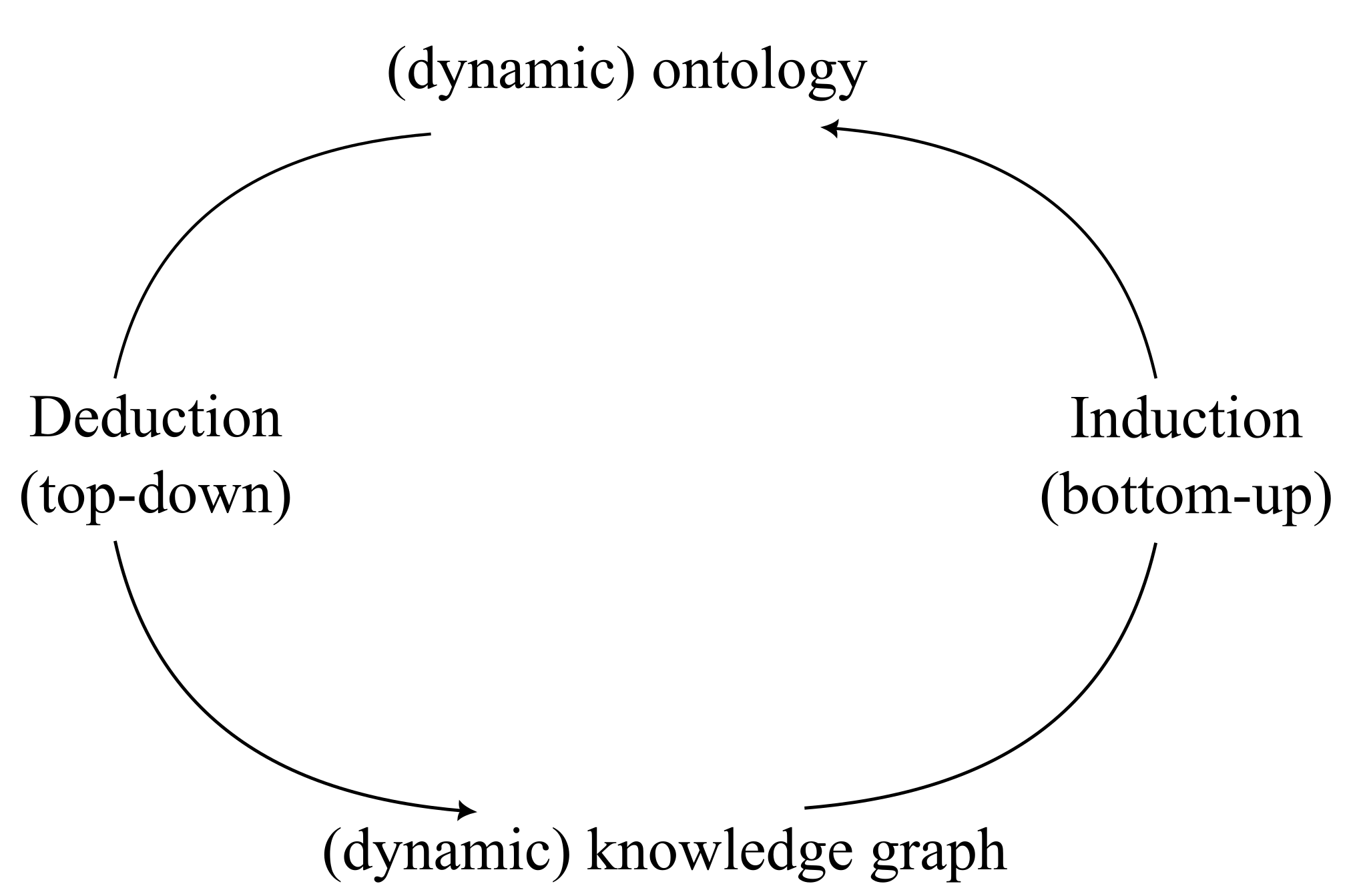

Inspired by Chomsky’s linguistics, there is work on learning a language-agnostic tree-like structure to learn embeddings of text, called Self-Structured AutoEncoder. This tree-like structure combines bottom-up composition of local contextual embeddings with top-down decomposition of fully contextual embeddings to learn in an unsupervised routine. Self-StrAE achieves competitive autoencoding performance with respect to a LLM, BERT-Based variant, denoting its low parameter efficiency that reflects the parsimonious nature of grammar.

Given the parallels with language, it is interesting to explore how would it work if Self-StrAE is applied to a DNA, or RNA sequence. What will the learnt structure tell us about the DNA sequence. Learnt embeddings would shed light into sequences of DNA which may have fucntional similarities. The compositions found by Self-StrAE would also find sequence motifs, which are short recurring patterns of DNA that map to specific biological functions like protein docking, because of frequent coocurrence leading to similar embeddings.

Language respects constraints, so does biology

Another interesting parallel are the constraints underlying both generation of sentences and biological entities/processes.

Imagine that you want to generate sentences. You have a collection of sentences to train a probabilistic model on. Because we can’t control what the probabilistic model learns from the given data, how do you make sure you don’t generate an ungrammatical sentence like “jogging Octopie went”, where we have a “verb-subject-verb” structure. The simplest way would be to set up a hidden template like “subject-verb-object”1 in order to offset portion of the probabilistic model’s support2 to not put any probability mass to structures other than “subject-verb-object”. Given this, this will first guarantee that sentences follow the correct grammar rules, and second guide learning since the model is not exploring over the whole parameter space, but only that which conform to the supplied template.

Consider the following analogous task, given some atoms like hydrogen, carbon, oxygen, among others, you want to train a probabilistic model to predict the angle of rotation when such input atoms are assembled together into a compound. This could be relevant for a 3D reconstruction of an assembled molecule. You have a dataset of different atom-atom compounds with their associated rotation angles. If you only rely on learning, then the resulting probabilistic model may put probability mass on biologically implausible rotation angles, even if that implausible probability mass is negligible. In the end, statistics is just about counting and averaging, meaning that even if you only see that some compound like water has a bond angle of around 105 degrees, the model’s support would still put probability mass in-between 0 or 200 degrees 3. Enumerating all possible rules concerning rotation angles would be impractical, so one can resort to biomedical ontologies.

Arguably, this is how DeepMind’s AlphaFold ensures that proteins generated from DNA input sequences are biologically plausible, as can be observed in the model’s pipeline. In it, the input sequence first goes through a database search that is subsequently converted into embeddings used to generate the protein structure. Without this first phase, this probabilistic model may output proteins that resemble the ones observed during training, at the risk of following impossible configurations.

Generating implausible proteins, or invalid angle rotations between bonds is akin to generating sentences that violate grammar rules.

It is debatable whether the rules can be learnt from data. Rather, the role of rules and constraints might be to shape learning.

For further thought experiments, imagine whether a model can learn what are the rules of programming languages by only observing code, or infer the rules of grammar from just observing written text.

NLP inspiring future biomedical research directions

A dictionary with mostly indisputable grammar rules are akin to biological ontologies like the Gene Ontology An interesting thought experiment hence, is can this grammar be expanded given the text available, analogous to asking whether

Final thoughts

I believe that because we can natively read Human language, research on NLP is more commoditized and well-received by the public than computational genomics, despite the parallels outlined above. I think it is worth for me and anyone interested in computational biology to closely follow the research literature on language modelling to draw inspiration ofr DNA/RNA sequence modelling.

Finally, I leave you the following thought experiment: we humans can only read human language. While we can not natively understand the language of biology, our AI-based tools can understand them.

‘AI may just turn out to be the language to describe biology’ - Demis Hassabis’s statement

If you have answers, share thoughts, you can leave a comment or please email me!

-

Sentences don’t follow this simple template, but it helps get the idea across that placing structure into the support of a probabilistic model helps guide learning. ↩

-

A probabilistic model’s support refers to the domain of values for which the output of the model is non-zero. ↩

-

While it is true that some bonds between atoms like a carbon-carbon bond have no restricted rotation angle, others like a hydrogen peroxide is constrained to a setting of rotation degrees (with some uncertainty). ↩

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: