Goedel Benchmarks: self-improving benchmarks

On the Leaderboard Illusion

For many conceivable scenarios where we face the dilemma of deep learning model choice for deployment, we would entourage around an authoratitive benchmark to compare the performance of different models on it. For example, in the realm of large language models (LLMs), their language comprehension is thoroughly evaluated by a benchmark suite, including the Chatbot Arena, where users can freely chat with a pair of anonymous LLMs and rate how good are their responses. A high “scoring” LLM on the benchmark can thus serve as the cornerstone of trust which we confide on to deploy it within a real-world application.

Nonetheless, as time passes by, new challenges arise. The issue with these (centralized) reputable benchmarks is that they invite practices of metric-hacking. Taking Chatbot Arena as an example, the study “The Leaderboard Illusion”, authored by Shivalika Singh et al., pointed out how such a challenging benchmark can be permeated with practices which inflate a LLM’s performance, including but not limited to forms of overfitting to the benchmark’s distribution.

There are many fixes proposed in the literature to address the problems, such as testing on multiple benchmarks instead of relying on a monolith “gold standard”, or disclosing evaluating practices so that the community can better judge a model’s performance by understanding how it was evaluated. In addition to the aforementioned, we propose the concept of a “Goedel Benchmark”, a self-improving benchmark which becomes more challenging over time. This idea of self-reference stems from a paper written by Prof. Schmidhuber regarding the design of self-improving problem solvers.

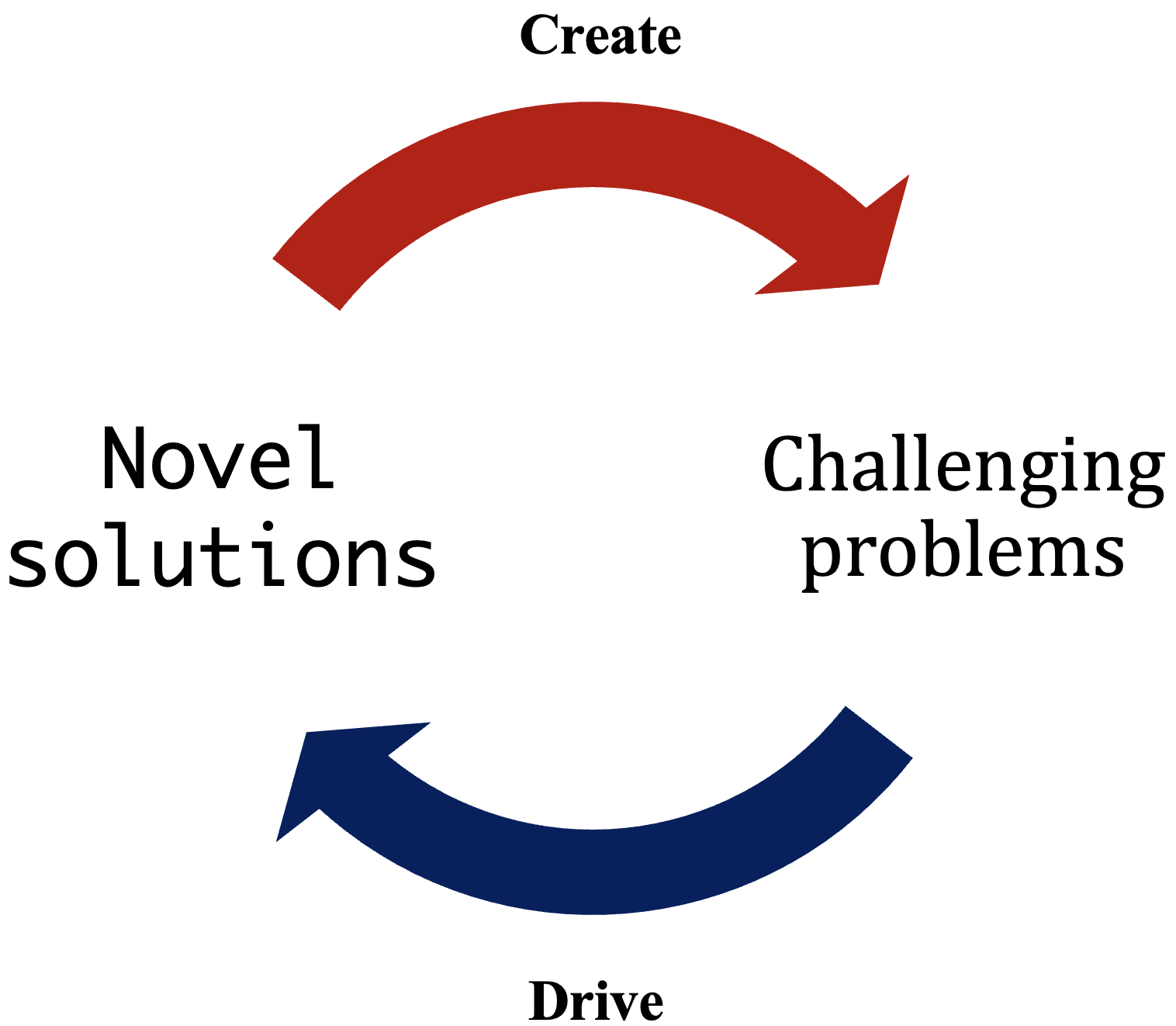

A Goedel Benchmark differs from current benchmarks in that it has no static training-testing distributions, thus mitigating issues driven by metric-hacking which opens the possibility to overfitting to the test distribution. This can be achieved by a method discussed in a previous article where a benchmark consists of:

- some generator which generated challenging tasks

- the solver (the model being evaluated) which solves the task and feeds it to the generator

- in this way, the generator learns to generate more challenging problems over time.

This benchmark is “dynamic” in that it’s not a closed set of question-answers. Rather, its current set of problems (and the solutions proposed by evaluated models) evolve tangentially to each other. The Goedel Benchmark also draws inspiration from Prof. Stanley’s “novelty” search, in that it evolves without a fixed direction, instead renewing itself with each iteration to stay perpetually innovative. In this regard, it’s not per se “accurate” to describe the benchmark grows to be more “challenging”, rather, it grows to be more “novel”. Said otherwise, each new iteration of the benchmark simply becomes distinguishable with prior iterations.

Finally, since a Goedel Benchmark is not static, performance in it can not be conveyed by a single metric. Instead, we resort to trends to represent a model’s performance on a Goedel Benchmark, where a “positive” trend (i.e. a model which can solve more challenging problems over time) can be considered by the community as a high-performing model.

Bibliography:

-

Schmidhuber, J. (2003). Goedel Machines: Self - Referential Universal Problem Solvers Making Provably Optimal Self - Improvements. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/pdf/cs/0309048

-

Singh, S., Yang Nan, Y., Wang, A., D’Souza, D., Kapoor, S., Ustun, A., Koyejo, S., Deng, Y., Long Pre, S., Smith, N., Ermis, B., Fadaee, M., & Hooker, S. (2025). The Leaderboard Illusion. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2504.20879?context=stat

-

Stanley, K. O., & Lehman, J. (2015). Why greatness cannot be planned: The myth of the objective. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG Switzerland.

Any comments? Feedback?

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: