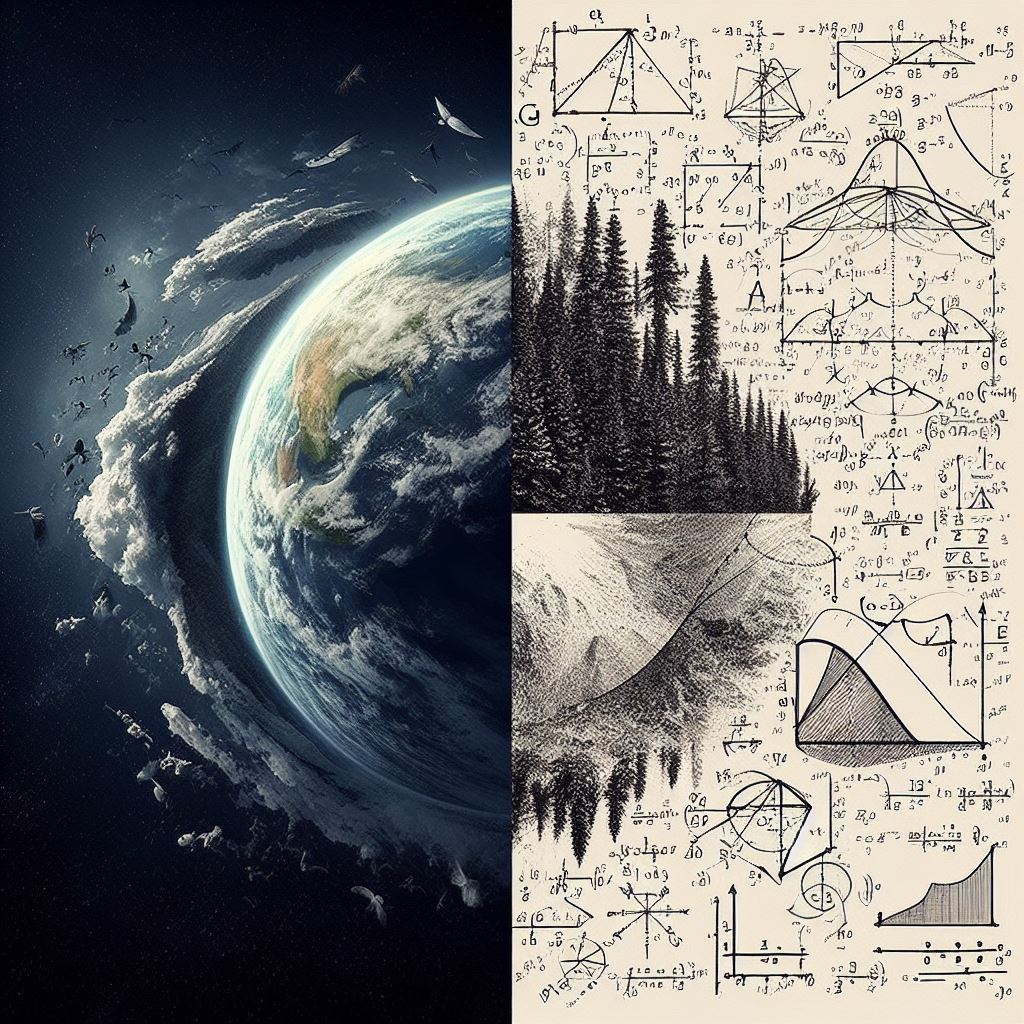

A tale of two worlds: the natural and the mathematical

I argue about the complementarity of math and the natural world, about nativism and empiricism, and implications of rejecting either of them.

There seems to exist two worlds which exist in the universe.

The real, natural world which can be accessible through empirical means, and the abstract, mathematical world which are the means themselves with which we observe the real, natural world. Here, the real, natural world is what we can perceive with our senses. The mathematical world is an umbrella term to refer to the ‘math’ in our common day parlance, as well as including logic in its many forms: propositional, first-order and higher-order.

The real, natural world is subject to the laws of physics, which underlie chemistry and biology. In the abstract, mathematical world, such laws are not present: there we can think of breaking Newton’s Universal Laws of Gravitation, the overall decrease of entropy against the Second Law of Thermodynamics, or, in general, anything within our mental capabilities1.

To recount this tale of two worlds, we can take a step back to ancient debate of nativism and empiricism

I argue this is a false dichotomy, and that underlying it there is the complementarity of nativism and empiricism. Nativism mostly deals in how the human mind navigates the internal, abstract, mathematical world. If we want to prove that there exists infinite primes, nativists would argue that such theory can be proved via universal inference procedures such as proof by contradiction, and manipulating symbols involving the definition of primeness of a number. In such an scenario, empiricism would say that we have to extrapolate from prior observations of prime numbers to conclude they’re infinite. However, who can live for infinite amount of time in order to witness the infinity of primes and assert the above theory! Another example would concern Goldbach’s Conjecture, which proposes that all even numbers greater than two are the sum of two primes 2. Can we prove it by observing all even numbers, as nativists would argue? I don’t believe so, we have to resort to the mathematical reasoning mechanisms we were endowed in our mind. One way is to prove it by contradiction. Assume there aren’t infinite primes, multiply the finite primes, and add one. This new number is not divisible by any of the finite primes, and thus is a prime. Infinity is a concept easier to understand and grasp when it is defined, as it can’t be learnt.

However, we Homo sapiens don’t only reason about the mathematical world. We use math to understand the external world, and understanding the external world recquire experiencing it, and with experience comes learning. Empiricist, thus, can explain how we are able to sort out the relationships of objects in the external world as a form of interpolating and extrapolating observed evidence. However, empiricists need nativists as much as the latter need the former. Empiricism need the structure of nativists to accommodate the perceptual stimuli of the external world in order to reason about their relationships and derive new ones. Nativists need to learn from external stimuli so that the structure can evolve and be able to describe more complicated relationships.

The natural world needs math to be understood, and math needs the natural world to exist. From this complementarity, it is argued that the mind consists of a grammar or a domain-specific language with which to give shape to thought

Implications of rejecting either nativism and empiricism

I advocate that there exists complementarity between the mathematical and natural world. However, I can’t stop others from opting for the dichotomy between them, thus not only pitting nativism against empiricism or the other way around, but also rejecting one at the cost of the other.

If we ignore nativism, and assume past experiencies are all that is needed to understand how the mind deduces new knowledge, we can think of the following. We can’t give shape to the mathematical world. It doesn’t “exist” in the real world. Circles, polygons, numbers, operations, vectors, matrices, infinity, among others, all reside within our mind. A friend once pointed out that he can draw a line on a dining table3 with a marker, and that’s a geometrical line. I disputed: “that is ink placed on a surface, which in your head is representing a geometrical line. While the ink and wooden surface are tangible objects, the geometrical line isn’t. Miraculously, however, I can also see and understand what you’re thinking concerning geometrical lines, suggesting the universality of math in the minds of Homo sapiens” (I may have edited my response to sound wiser, as well as edited the whole story to make it more entertaining).

That math doesn’t exist in the real world, and thus can’t be picked up with our perceptual systems can explain why large vision models like DALL-E or MidJourney struggle with generating images which contain letters or numbers, unless they are fed with prior knowledge on characters

We also can’t accept nativism at the expense of empiricism. The history of artificial intelligence is a good reference to observe that resorting to only expert systems consisting of universal inference rules like forward and backward chaining results in systems that are disconnected with real world dynamics. Whilst math can be independent of the real natural world, it is nonetheless intricately connected to the world in order to describe it.

Implications on the quest for artificial intelligence

Deep learning ignited the summer of AI of the twenty-first century, and the transformer is one of the torches that keeps the summer shining. How should we keep this summer from ending?

Deep learning is a mostly pure expression of empiricism. Deep neural networks don’t manipulate symbols, are inspired by the brain’s architecture, and are mainly learn via training from a dataset of past experiences. There are several empirical observations, and reductionist

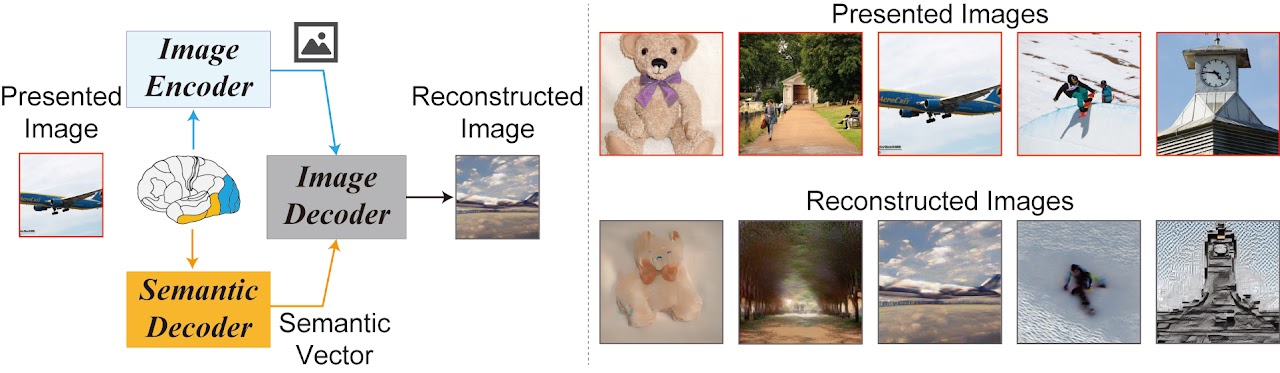

That there is some association between brain activity and external stimuli capturable by a probabilistic model is fascinating and encouraging for empiricism. However, most if not all research related to the neuroscience behind mental activity lacks the explanation of whether brain activity yields any insight into mathematical theorem proving or deduction. Experiments to explore this can involve assessing whether brain activity can reconstruct a person’s steps into solving an equation, deriving a proof or just in general have some abstract thought involving numbers.

Furthermore, taking empiricism to an extreme may stifle the capabilities of an AI model, since radical empiricism subjects the model to be an extrapolation from supplied past experiences. It ignores the nativist capability of generating new thought, often called as creativity.

Another counterargument to empiricism is also as follows. Image there is a program running on a computer. You can observe your program running on the screen, as in, you can see what input matches the corresponding output displayed. You also know the underlying algorithm specifying how the input should be transformed to the output. Now, you disassemble your computer and expose its mainframe, now able to look at the CPU and RAM running, all the while your program keeps running. In other words, only the computer screen is gone, so any high-level display your program disappears. You invite an empiricist and tell her that she can make all sorts of measurements she wants on the hardware of the computer (CPU, RAM, motherboard, graphics card). Such measurements could include voltage, heat maps, temperature, and whatever she can think of. Of course, because the computer screen is gone, and she is prohibited from reassembling it back, she is restricted to measure the low-level components of the computer. Now comes the main question, can she be able to figure out from measurements made on the hardware the algorithm being executed? Here, the computer and its low level components correspond to the biological brain, and the software is analogous to mental activity.

While low-level activity can reflect to some degree higher level processes, I’m skeptical we can understand and simulate higher-level cognition without assuming its pre-existence. Therefore, we can only describe high level mental activity with high level mental activity. In the thought experiment, this would entail the empiricist may have to ‘hypothesize’ in a separate computer different programs that could be running in the monitor-less computer, use feedback from the low-level measurements obtained from the monitor-less computer, and find which hypothesized programs matches the measurements from the monitor-less computer. Such iterative process of trial and error, which combines both the high-level cognitive process of creativity and low-level signal processing for feedback.

As argued repeatedly, the brain’s architecture, neuronal activations and modifications in synaptic strengths all belong to the external world. Drawing inspiration from the brain is a powerful means to achieve AI. However, mental activity such as deduction, and emergence of new ideas through conjecturing

Final comments

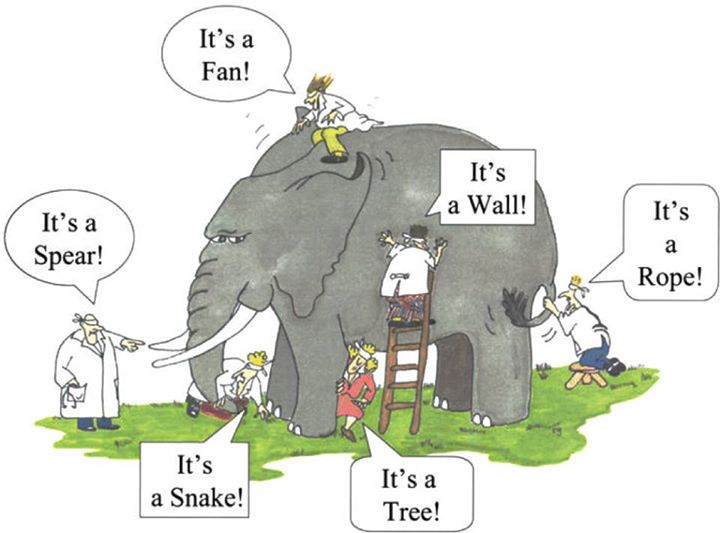

When I just learned about the scientific method, my colleagues and I were told of the story of “The Blind Scientists and the Elephant”. Each one of the scientists had to rigorously examine a part of the elephant in front of them and conclude what they were looking at:

Nativists and empiricists are analogous to the scientists, and the brain is represented by the elephant. It is not the case that both hold opposite views. Rather, they are providing explanations to different aspects of the mind: empiricists focus on learning, and explain that the brain’s neuronal activity-associated synaptic changes can encode knowledge from the environment. Nativists are not opposed to this, per se. They are just looking at other aspects of the mind: the abstract, intangible portion which deals with the manipulation of math. Math is perhaps a faculty that is native to Homo sapiens and is the basis of thought.

-

what I listed above mainly involves equations with real and maybe imaginary numbers. However, what if there is more to these types of numbers that we haven’t thought of, or we’re incapable to even comprehend? Because this question is off-topic, I left it as a footnote. ↩

-

the easier version proposed by the Tortoise from Gödel, Escher, Bach is easier to prove, which states that all even numbers less than or equal to two are the sum of two primes. ↩

-

he didn’t clean it afterwards ↩