Reflections on the Neurosymbolic Summer School 2023

I attended the NeuroSymbolic (NeSy) Summer School 2023 held virtually between August 29-30. What follows are my thoughts and comments with regard to some talks. They can be watched thanks to the available recordings, which provide context for the ideas below:

Reflection on talks by Professors Benjamin Grosof, Fabrizio and Fabio, and Luc de Raedt

They mostly talked about the use of logic, propositional or first-order, to shape a problem domain and drive neural networks to make explainable predictions, discussing the strenghts and drawbacks of this approach.

I am personally skeptical of the use of logic to encode knowledge or describe relations. This is because there exists infinite knowledge, and thus this entails that in order to solve real-world problems that involve complex systems, e.g. predicting cell progression in a tissue, may involve writing infinite amount of rules encompassing cell physiology or pathogenesis. It is also disputable what are the putative rules to encode in order to solve problems, and rarely two experts on the same field may converge on what rules should be encoded into a model for solving a problem like cell trajectory analysis. On a tangent, I also liked the point raised by Prof. Benjamin Grosof on defeasible knowledge, referring to rules which are only true circumstantially. For example, for a rule like ‘every cell has a nucleus’, this is only true when the cell is not going through anaphase of mitosis or if it’s a bacterium. One can relax the “absoluteness” of rules using temporal logic (‘something is true during certain timeframes’) or by encoding probabilistic knowledge, i.e., rules attached with probability distributions on their truth values. However, these only exacerbate the inherent combinatorial search space related to the search for rules that can answer a query.

Let us illustrate with the following hypothetical logic program:

friendOf(kerry, natalia).

friendOf(natalia, shirley).

smoker(natalia).

emphysema(natalia).

smoker(X) :- friendOf(X, Y),

smoker(Y)

emphysema(X) :- smoker(X)

query(emphysema(kerry), ?)

Given a knowledge base, there is knowledge that is already available (written explicitly in the knowledge base), which is a subset of the Herbrand Base of the knowledge base, namely all possible knowledge that can be deduced given the rules and available facts. For example, the Herbrand Base above would include that Shirley is a smoker given that she is a friend of natalia, therefore Shirley has emphysema. The same with Kerry: he is a smoker since he is a friend of Natalia, and he also has emphysema. If we annotate facts and rules with probabilities to turn into a probabilistic logic program, then this exponentially expands the size of Herbrand Base. Let us just say that Kerry is a friend of Natalia with probability of 0.6, which cascades into Kerry having emphysema with some probability. Given the annotated probabilities, this, in turn, means that there is 0.4 probability he isn’t, which cascades into another series of possibilities where he might be or not be a smoker, depending on the probability annotations for the rule of smoker. You may also disagree on whether this should be the rules written to model this simplistic world. And you can also wonder how such a setting scales in terms of complexity if we aim to solve problems concerning complex biological systems.

Furthermore, another problem with encoding logic into a model is that it assumes the expert or researcher knows a priori what knowledge to encode. What if I don’t know how to write correct logic program, and how would I know whether it is incorrect?

If not knowledge, then ?

My criticism towards this kind of logic is that it doesn’t reflect the complexity of the real world. Namely, in the real world, there exists infinite knowledge yet to be discovered. I believe it is not the case that a human brain stores knowledge since there is infinitely available.

Rather, I believe that the brain stores operations/programs which operate on the world to obtain knowledge. In other words, it doesn’t store knowledge, it scaffolds from the environment to obtain knowledge. For example, it is not the case that a Herbrand Base of some logic program is stored in my brain, rather, inside it there are programs, such as modus pollens and modus tollens that allow to process this logic program that is written on the screen in front of you. What is interesting about this is that, for example, Shirley the person is not stored in my mind, she exists on the real world. What is actually in my mind is an operation like modus pollens, which when applied on her and her smoking habit, allows me to deduce she is a smoker. Perhaps the rule of whether she is a smoker is encoded in prior exposure to social dynamics of friends and smokers. Here, the encoding procedure, the manipulation of social dynamics and smoking habits can all be thought of as programs.

Another source of beauty with programs is that one doesn’t need to write rules, but rather a domain-specific language with grammar rules for the machine to use it as its language of thought to interpret incoming data. As an analogy, I like to think of it as defining a programming language, where a machine learns to understand the world by writing and editing its own code, a form of self-reference.

Furthermore, I hypothesize that perhaps we need a vector embedding for primitive programs and their compositions. Empirically, it has been observed that continuous representation of discrete symbols/concepts tend to speed up their manipulation by exploiting GPU parallelism, such as searching over them.

Interesting work revolving on program synthesis include neural module networks, and an improvement over this architecture.

Reflections on talk by PhD student Abulchair, and Prof. Guy Van den Broeck: Can LLMs learn to reason?

Agreeing with Prof. Guy, I’m skeptical of the idea that large language models (LLMs) can reason. There is no precise definition of reasoning in the first place, but it at least involves searching over a space over all possible knowledge attainable from the current knowledge you have. Reasoning involves hypothesizing (composing new, but possibly invalid, knowledge from existing knowledge), validating with data, and staying consistent with such knowledge.

Through reasoning, you should be able to search and derive knowledge that is out of distribution of the available data.

On the other hand, because LLMs are statistical models, it is imprinted in their design that they can only estimate a probability space that approximates to the training data’s distribution through counting and averaging. Assuming that the test distribution can always be different to the training data distribution, then I’m unable to be convinced that LLMs are able to overcome the inherent incapability of addressing the inability to generalize out-of-distribution of statistical models.

I think that only if the future is the average of the past and present, and there can be nothing novel emerging from them, then statistical models would be good simulators of the production of knowledge. However, the growth of knowledge does not happen as a continuation or reflection of past and present knowledge.

That is why NeSy AI is an interesting field regaining attention as it seeks to integrate neural networks with the capability to reason (whatever that means), and achieve good performance on out of distribution tasks.

Reflections on talk by IBM Researcher Michael Hersche: ResNet vs. RAVEN Progressive Matrices

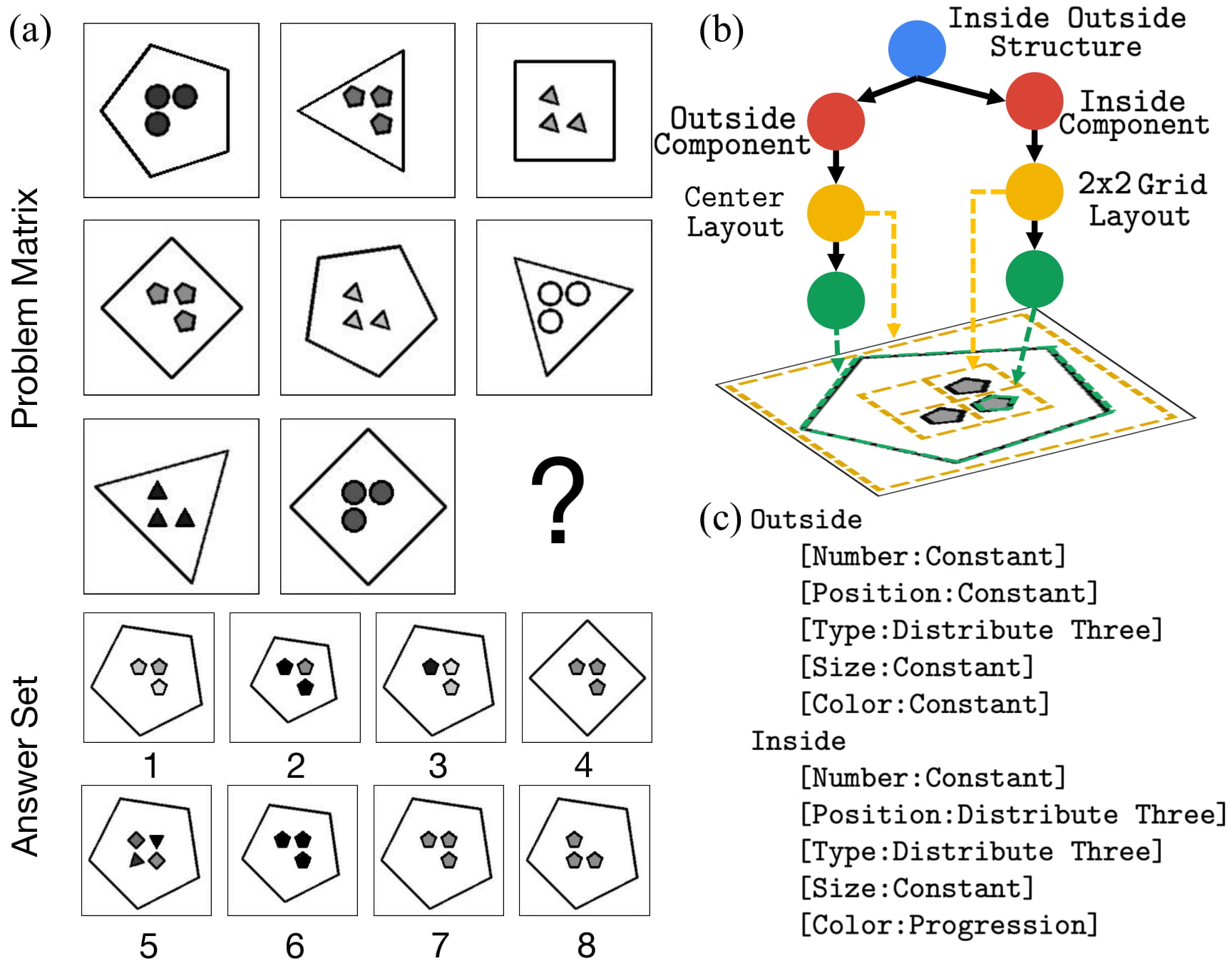

RAVEN is a dataset that aims to simulate an IQ test for deep learning models:

IBM Researcher Michael Hersche managed to train a convolutional neural network with encoded rules appearing in the RAVEN dataset that succesfully solved it. However, as pointed out in a later panel discussion, the assumption is that the researcher knows beforehand what primitive rules underlie the generation of the implicit patterns in the progressive matrices.

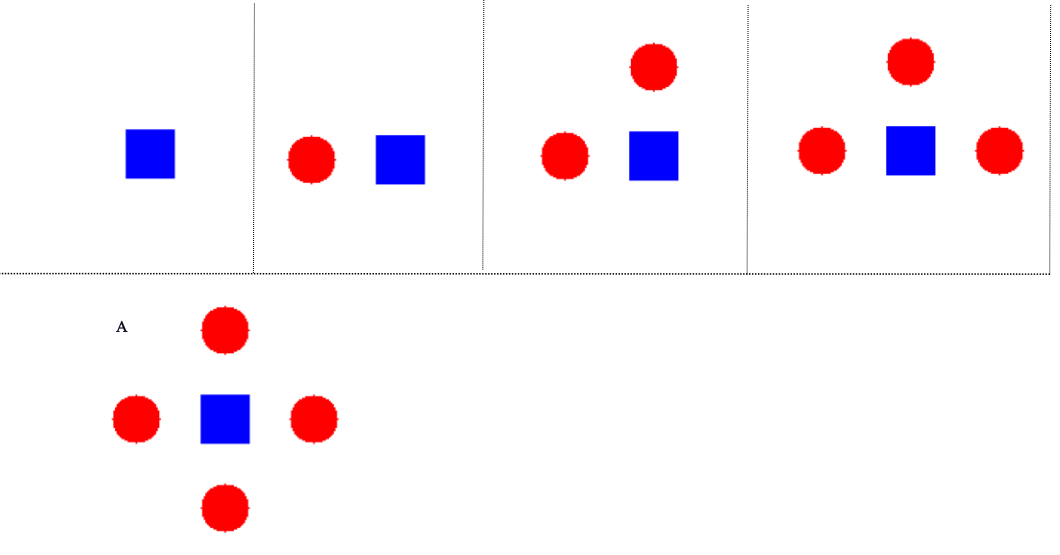

To mitigate this, I’m keen in observing whether NeSy architectures can tackle the still unsolved Abstract Reasoning Corpus(ARC) by Prof. François Chollet. This is a more challenging problem, because first there is no correct answer to choose from multiple choices, and thus ensures statistical models don’t exploit artifacts of the problem setting. Instead, the model have to generate the correct panel given prior pairs of observations. Furthermore, and most importantly, there is a new underlying pattern every few training examples, and patterns appearing in the held-out test set never appear in the training set either:

In my undergraduate dissertation, I proposed combining different datasets into a single benchmark suite for heterogeneously testing the capabilities of NeSy methods. One of the tasks involve assessing abstract reasoning, which is jointly inspired by RAVEN and ARC:

Reflections on the talks by Professors Chris Potts, Yoshua Bengio

Will deep learning ever be transparent?

The main constitution of deep neural networks is its parameters stored as values in matrices across layers. Will we ever be able to distill discrete concepts from such matrices?

I doubt so. We can ask instead whether humans are interpretable, i.e., whether our neuronal activations are seldom explainable…

There is research suggesting that perhaps neuronal activations do shed some insight regarding real-life perceptual stimuli, e.g., think of the grandmother cell which is a quotidian example that says that on average, a certain neuron of the brain fires whenever the corresponding human subject is exposed to a stimulus related to the subject’s grandma. For more interesting research associating neuronal activation to external stimuli, please read the Science magazine article reconstructing audio, or using generative AI (diffusion models) to reconstruct images from human brain activity.

However, most of the research is restricted to reconstruct external stimuli.

I am now curious as to what are the neuronal activations corresponding to someone proving the Pythagoras theorem, or the sequence of neuronal activations associated to proving the Goldbach conjecture? I ask because mathematical reality is different perceptual reality.

Deep learning, language and truth

An interesting point raised above concerns statistics and the truth of a collected dataset. During the talk, it was mentioned that the learning the joint distribution of words is not the same as learning truthful statements. Consider the following example:

\[P(\text{the newborn is female}) \neq P(\text{joint occurrence of tokens 'the newborn is female'})\]My comments on some audience members’ questions

There were very interesting questions raised through talks and panels I wished to share my thoughts on:

Applications of Knowledge Relational Reasoning

A colleague asked on the applications of knowledge relational reasoning. I think you can deploy knowledge bases, knowledge graphs or relational databases (which are subsets of logic programming) that can be used to manage a process pipeline in a business, such as price tagging, or moderation of security measures.

Are neural networks propositional?

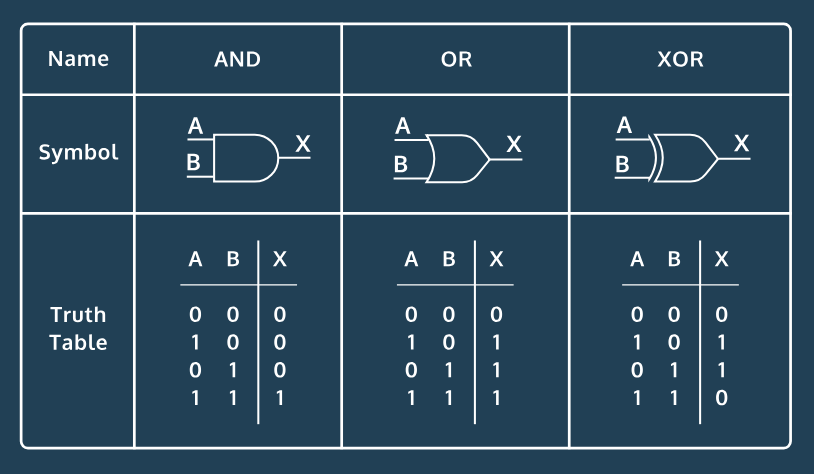

I interpreted this question as whether neural networks can perform propositional logic, to which I’m skeptical. It is true that in the early history of neural networks, they were used to approximate simple functions representing logic gates, such as AND, OR and NOT gates, often from a small dataset of just two or four datapoints. You can even estimate this by hand to see backpropagation over a single layer network in action. It was later discovered that eeeper networks, in terms of number of hidden layers, could compute more complicated gates like NAND or NOR gates.

Nonetheless, whether this entails that neural networks can emulate inference in propositional logic is debatable. For example, see experiments and analysis done at the paper by Honghua et. al, “On the Paradox of Learning to Reason”. TL;DR, neural networks, no matter how deep they are, can’t generalize to out of distribution test data in a simple propositional logic task of reasoning.

Do humans actually perform forward and backward reasoning?

I think it depends on the context. For proving mathematical theorems, humans arguably perform a reasoning procedure which is represented by implementations of forward and backward reasoning. In other contexts, such as finding the closest emergency exit during a natural disaster, or driving, there is another form of (fast) thinking which is unlikely captured by forward or backward reasoning. This idea is extracted from Daniel Kahneman and Toversky’s book on Thinking, Fast and Slow. The brain is indeed amazing on being able to switch modes of thinking, such as between intuition and reasoning.

Will brain research lead to engineering wonders that far surpass the brain?

A member of the audience appealed to the bird-airplane thought experiment: will something similar happen to the brain-computer relationship, i.e., we can design an algorithm ran on a computer that is devoid of the flaws of the brain, such as the brain’s limited lifespan, biological constraints, and obtain a tool that is far more powerful than the brain itself. This is analogous to how an airplane, despite having its architecture inspired by the phenotype of the bird, is many scales more efficient at flying and carrying cargo than any existing bird.

First, I think the analogies are flawed at its core if we want to discuss on the topic of intelligence. While the airplane succeeds at a particular task of flying over long distances, it is devoid of intelligence and is dependant on the human flying it. In some regard, intelligence perhaps is not just about solving a task. Without a human operator, an airplane that is about to crash, or goes low on fuel, has absolutely no way to adapt to changes, and formulate a plan to get out of its predicament by itself. Birds, on the other hand, can engage in simple problem solving concerning survival, reproduction and caring for the young, all while adapting to circumstantial events in their environment. One striking example that is often cited by Prof. Song Zhu-Chun is of a crow that can take advantage of incoming cars to break nut shells and eat them.

However, once we have grasped the dark matter of intelligence in a model, then I think scaling it up will lead to wonders that we can now only envision: supercomputers able to manage cities, accelerate scientific discovery such as in the biological sciences and take us to Mars.

What is hardcoded in the brain?

I think humans’ capability to think of math is hardcoded, and this is the main distinction between us and non-human animals. By math, I don’t just mean counting, but rather have the fundamental principles of arithmetic encoded in our mind. Moreover, I believe this underlies universal grammar.

Conclusion

Hope you enjoyed the summer school, and please leave any comment, feedback or points for discussion! Happy learning!

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: