Review of the paper Prediction of mechanistic subtypes of Parkinson's using patient derived stem cell models

comments on a paper that leverages deep learning to classify cells into Parkinson's subtypes

Brief summary

The paper by

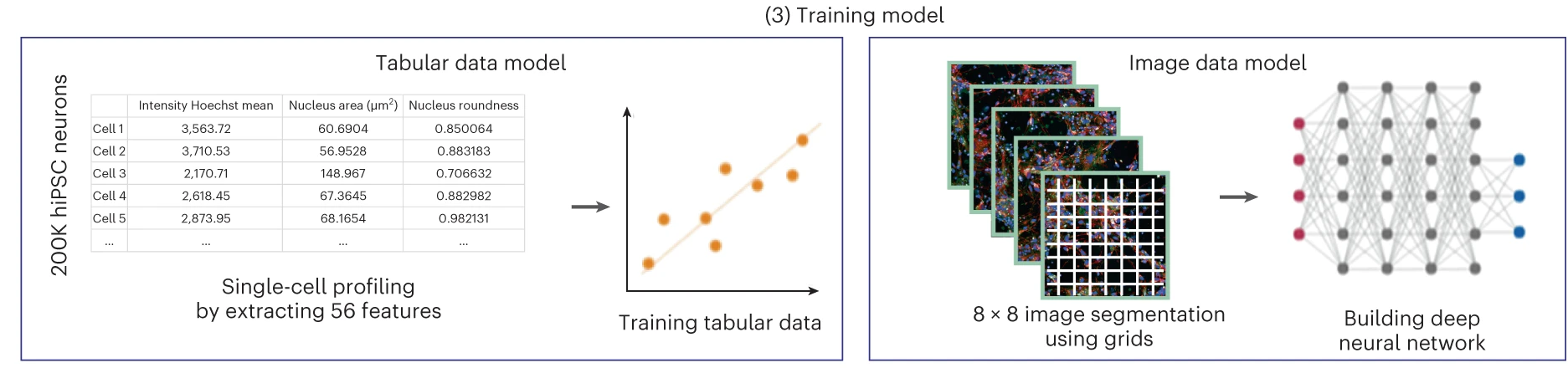

The research team trained separately a dense feedforward neural network (DNN) to classify on the tabular data, as well as a convolutional neural network (CNN) to classify on image data. The test classification accuracy achieved by the DNN reached around 83%, while the CNN 95%.

My comments and future research directions

Generally, in the deep learning literature, it is acknowledged that the usage of DNNs comes at the expense of poor explainability. Despite achieving high classification accuracy, these models are black-boxes. Nonetheless, there are ways to identify what are the features that the neural networks pay the most attention when deciding on a classification label, mainly by looking at its last layer’s activation and tracing back to the input space which input feature is associated to it. In CNNs, the technique employed by the research team is called the ShAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) method.

The authors managed to identify in both the DNN and CNN that the mitochondria, lysosome and the interaction of both features mainly contributed to the classification decisions of both models.

One future research direction I am interested is exploring whether by integrating both data sources can improve performance and yield explainability, because the original work trains separate models, trained on different datasets.

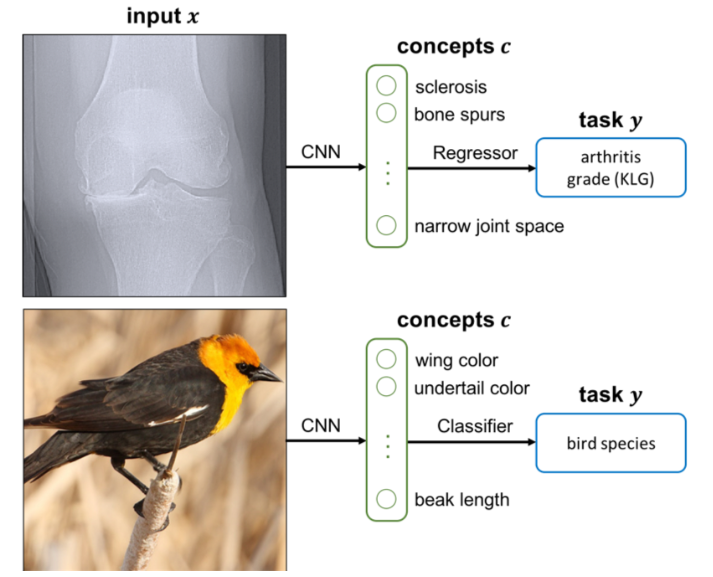

One source of inspiration is from

Altogether, with regards to the work by

As a further improvement, we can use a Slot Transformer instead of the CNN with the hope of learning a disentangled representation given the image with its annotations. However, the architecture will be more computationally expensive. A pretrained Slot Transformer that already learnt to disentangle CLEVR-Scenes may be more powerful than training it from scratch.