Review on Sapiens and Homo deus by Yuval Harari

my review on Sapiens and Homo deus, books authored by Yuval Harari

Overview

What does it mean to be human? What does it mean to exist? What is being Homo sapiens?

Sapiens

1. Intolerance and our drive to change ourselves

How did we arrive to the present?

Some of the intriguing questions that were discussed in Sapiens is why Homo sapiens is the sole species that stood until the present day to become the most powerful organism governing every other remaining species. Indeed, it was strange to me that given the existence of Homo erectus or Neanderthal, why is it that Homo sapiens is the only one that remained.

A viable hypothesis is that a fundamental trait, albeit not unique, of Homo sapiens is that we are intolerant. Our intolerance to different species is what perhaps drove our competitive and lethal behavior that may have extinguished these species. The remnants of such intolerance that we inherited from our ancestors can be perhaps witnessed in how today’s humans can still get at each other’s throats for trivial issues such as different ideologies or ethnicity. Not even a century has passed since World War II has ended.

Of course, intolerance is not necessarily something to be viewed as exclusively negative and something that ends up guiding Homo sapiens to engage in brutal competition or deadly fights to emerge victorious until the present. Intolerance is also what perhaps drove us to achieve our current advances in technology, and build highly efficient civilizations that permit the exploration of outer space and soon the colonization of other planets. Here, I’ll use a very intuitive definition for intolerance, which is to not conform with a present situation. In Sapiens, a recurrent theme throughout the book is that a lot of the commodities we have nowadays, such as a personal computer, smart phone, public transportation, hygiene, a society with all of its institutions such as schools, business corporations, among other things, aren’t actually necessary, at least in terms of biology. Our basic biology can be simply satisfied by an adequate supply of food and reproduction through finding a partner. In short, survival and reproduction were perhaps the fundamental reason to exist since Homo sapiens, and by that regard any other species, appeared on Planet Earth. What makes Homo sapiens distinct from other species is that we don’t only behave within the boundaries set by our natural, objective needs of survival. We can step beyond our biology and interact with the environment and with each other to manufacture new purposes of life, new subjective needs (in the book this process was known as revolutionizing our cognition). Art, religion, science, economy and politics, and along with it war and poverty all emerged partly due to our intolerance towards the boundaries of the survival instincts that we’re born with. Conversely, we can imagine how simple today’s society would be if we only sticked to our basic, natural instincts of survival: there won’t be private and public institutions promulgating the rule of law, nor promoting scientific research and development to enhance our livelihoods. We might be simply roaming around the vast fields on Earth and preying on whatever sustain our being.

2. Mass coordination and our drive to become more powerful

The irony of human life is that although we’re intolerant to each other’s differences, we can nonetheless set aside such intolerance and achieve a very flexible, highly-efficient cooperation between one another to achieve great deeds that ultimately positioned ourselves not only on top of the food chain, but also placed us closer to space, the moon and other celestial bodies. In Homo Deus, another set of intriguing question involved asking why haven’t bees, insects that can organize so efficiently between themselves, built nuclear weapons like us humans did. Why haven’t elephants, or other species that have displayed some level of capacity to band themselves to fend off predators or cooperate between themselves, conquered humans like we conquer them. A viable answer to that is that Homo sapiens is perhaps the sole species in the entire planet (and maybe Universe), to efficiently make use of language to communicate with one another and coordinate ourselves into groups to deal with the dangers that other species and the environment posed to us. Here, the fabric that holds together this assembly of humans is something called intersubjectivity, as mentioned in both books (Figure 1).

Of course, one could be curious as to why the formation of this intersubjective, collective thought that mass cooperation is good didn’t lead Homo sapiens into living stagnant lives, without much change in their lifestyles as if it was in hiatus, but has rather guided this species into changing so much as to become the unabated top predator of the food chain, the undefeated organism that can conquer illnesses, explore space and is currently finding paths to immortality and create artificially intelligent entities. This is in sharp contrast with how Homo sapiens looked like ages ago. The fuel behind is perhaps what was discussed above: the intolerant nature that Homo sapiens was born with, and that is passed down through generations.

To understand the above, we can look at this from another perspective. We can imagine what would have happened if our ancestors didn’t have the capability nor desire to group themselves into large civilizations, but rather settle themselves into small groups of hunter-gatherers or small villages of farmers. In other words, they may have formed systems of believes that justified and encouraged some actions such as hunting and agriculture but didn’t really seek cooperation nor sharing these beliefs between themselves. If that’s the case there wouldn’t exist complex entities such as villages, nor empires, nor nations. We could also ask what if our ancestors did assemble at a massive scale by reinforcing this set of inter-subjective believes to form communities, villages, empires or nations. Nonetheless, this massively organized assembly wasn’t built with the purpose of changing its own status (for better or for worse), but rather to just maintain it. In other words, they banded into large-scale groups just to “watch the days pass together”, “contemplate the cycles of the sun and moon”, “hunt to survive, but don’t do anything else to disturb nature”, without ever asking whether one day a collective effort could revolutionize lifestyles, that collective effort could send humans to the moon, that collective effort could dominate any other ferocious species that may have once scared them or that collective effort could lead them to a different, better future.

Regardless of which scenario above is examined, it’s very likely that in each, we, Homo sapiens, may have been extinguished or conquered by a species that was capable of achieving that highly proficient level of mass coordination fueled by greedy-intolerant ambitions, similar to how we’ve sent countless other species to extinction by feeding on them or subverted other species like chimpanzees to zoos for entertainment and rats to laboratories for science. None other species, not elephants, nor bees, not chimps nor rats, who have indeed shown some level of mass cooperation, can organize themselves into such a succinctly designed assembly and be so well coordinated no matter how different they are like Homo sapiens. Let alone mention how other species other than Homo sapiens could have ambitions to improve their own situation, build intelligent machines, or explore outer space.

All in all, the synchrony between intolerance and mass coordination sustained by a collective, intersubjective belief may sound unstable, but it’s this beautiful myth that constitutes part of the reason of why us humans, Homo sapiens, achieved our current status in history, which is in sharp contrast with other species such as Homo erectus or Neanderthals that have gone unreasonably extinct, or chimps and fish, that have become subverted by us without obvious reasons.

Intolerance and mass coordination for artificial intelligence

On a completely different note, owed to my interest in AI, when reading about these fundamental aspects of humanity, it sparked in me an interest in how these aspects (mass cooperation, intersubjectivity, intolerance). Given the current progress in AI, we could ask intriguing questions as follows.

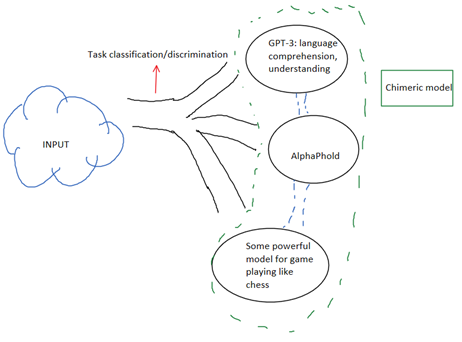

How would AI look like if the different models that have achieved landmark achievements such as GPT-3 or AlphaFold were to merge or cooperate between one another, just like how humans from completely different civilizations worked together in human history? This chimeric model (Figure 2) would be capable of performing diverse tasks depending on the input that it perceives. These tasks may range from reading comprehension to protein structure prediction, to disease prognosis and autonomous driving.

Of course, Figure 2 is just a rough draft from which a plethora of practical concerns arise: how many models will it have to merge? What are the boundaries of each model added? Is this architecture scalable? Among others. Nonetheless, the underlying analogy to draw here is that just as how different humans can cooperate at a massive scale, I envision that the next step to get closer to general intelligence is to somehow be able to merge all these different models or to form certain connection among them.

Harari has summarized quiet precisely that in biological terms, organisms’ sole purpose of existence is to survive and reproduce. Through natural selection, one species, like Homo sapiens, which is by nature intolerant and capable of achieving mass coordination through developing intersubjective believes, became the most powerful entity on Earth. Nonetheless, AI is not only not a biological entity, but also devoid of a purpose of existence. What are the “survive and reproduce”[^1] equivalents for AI, and how will AI evolve from those basic needs into also becoming “intolerant”, developing “intersubjective beliefs to massively coordinate” other AI models like the chimeric model in Figure 2, and subsequently displace Homo sapiens as the most powerful entity on Earth, or even larger, in the Milky Way or Universe. Therefore,

… from another perspective, will we be able to embed in a machine a value function resembling the survival instincts of human beings, such that this value function can somehow guide the machine into evolving and developing complicated, yet intricate networks of machines to cooperate with one another into further enhancing this value function?

With all the talk about AI above, it seems as if only we, Homo sapiens, shaped AI. Nonetheless, I believe we should be open to the idea that AI can also change us. For example, the pursuit of artificial intelligence has changed how we view intelligence, cognition, perception, among other mysterious human faculties that we don’t understand thoroughly, yet. AI, and its symbiosis with other sectors of society such as healthcare, education or economy will also have a deep impact in our lifestyles. Given this premise, we Homo sapiens can reflect on how our intersubjective realm is going to morph in response to how AI advances. Although Harari wasn’t specifically referring to AI, the following are quiet interesting ways to redefine some of the mysterious faculties we humans have:

- “feelings”: inaccurate term used to describe a collection of neuronal signaling. But then, I believe a natural question that follows then is what initiates this cascade of neuronal firing: external input, internal structure, or both?

- “Emotion”: a biochemical algorithm of neuronal signaling.

- “consciousness”: term to describe feelings and mental imagery (representation of our perception).

Theoretically, this suggests that with a digital neural network, e.g. a deep neural network, that’s meant to simulate neural signaling would be able to model these human traits, even if the end result is not necessarily “within our expectations of what feelings, emotion and consciousness are”. For example, to me, the advances of image recognition have provided me with the following definition to “understanding”, which is to be able to have some higher level neurons fire probabilistically in response to the low level firing of neurons given an determined input stream. This is in sharp contrast with common definitions that advocates “understanding” assimilated a “meaning” that’s associated to an entity of the world, or somewhere along the lines. Of course, although there seems to be a more down-to-earth, precise, biological and mathematical definition to “understanding” that may be in contrast to a lot of our expectations (including me), it seems as though this is where we might be induced to think due to the rapid development of AI that’s going against much of the paradigms we believed in the past and present. As a side node, I’ll fervently encourage all of us to think not in tune with the current norms, since in this way we tend to reinforce our current paradigms, but rather to focus our studies and reflections on what’s different to the norm, since in this way we can explore and inquire into the unknown.

It’s worth noting though that the above inquiries concerning the future development of AI revolves around our understanding of human beings, particularly Homo sapiens. Nonetheless, though Homo sapiens is very likely to be the dominant species in the world, it’s not the only one. The future steps could also draw some inspirations from other species as well. For instance, bats perceive the world through echolocation, so would this trait enhance AI?

But in the end… are we happy?

I have attempted to share my thoughts on Yuval Harari’s two books on how we came to be as we are today (due to our intolerance to how we’re born and to those around us), as well as discussed where we might be heading, mainly by drawing parallels with the development of AI. However, just like author Harari, I wanted to ask, are we happy? As in, are we happy about with our current understanding of human nature? Are we happy about how we envision where we might be heading? These are some questions that dissolves itself into the abyss of neglect during our pursuit of understanding ourselves and of higher grounds of humanity.

Of course, how do we define happiness to begin with anyway. Harari shared a simple definition, which is that happiness is a byproduct when our expectations meet reality, or vice-versa. We, Homo sapiens, have efficiently managed to survive until the present day, and through our intolerance to our previous selves, previous ways of living, we managed to climb to the top of the food chain and govern planet Earth. Nowadays, we’re in a crossroad where we get to decide to where we’re heading to, and whether the path chosen makes us happier, as in having our expectations driven by intolerance met, or make us more intolerant, as in having wilder, more ambitious expectations.

The questions I’ll want to ask of course in this final section, given the plethora of possibilities that the understanding of human nature and progress in AI bring, are:

Will our understanding of emotions and feelings help us become happier, or will it lead us to live in a society saturated by experiences such that there would be nothing else to make us happier?

Will the symbiosis of AI with the different sectors of society (Healthcare, Economy, Education, among others) satisfy our needs or just produce even more needs?

All in all, Sapiens and Homo Deus are two books authored by Yuval Harari that I highly recommend reading. Although both their themes don’t specifically revolve around artificial intelligence specifically, I’d also recommend wondering how our current understanding of Homo sapiens could shape the future development of AI. Of course, it’d be also fruitful to reflect on whether all this makes us become happier, or just makes us more ambitious to pursue happiness.