Spatial, temporal, causal and-or graph, the next step for Cognitive Science?

thoughts on an unifying framework for cognitive science

Please see Errata at the end of the article concerning the limitations of a chatbot

Searching for a unifying framework for addressing cognitive science

Cognitive science has shared parallels with artificial intelligence in the sense that it has also gone through “booming” periods, meaning times when a proposed theoretical framework seemed to be able to explain aspects of the human mind, and subsequent “busting” periods, times when that framework was rebuked by new findings1. Such booming and busting fluctuation revolved around the dichotomy between nativism and empiricism, with their respective ramifications2, but regardless of this rivalry, the 21st century lifted its curtains being able to find reconciliation between these two and propose yet another theoretical framework seeking to ultimately explain how our minds work, called Predictive processing (PP) (see

It’s important the seeking of a unifying basis to direct the study of cognitive science because it helps make its study coherent. Furthermore, in other fields such as that of Physics, as pointed out by Prof. Song, it has been noticed that current studies of this discipline revolves around the fundamentals of forces, fields and particles. In that regard, predictive processing, along with spatial, temporal, causal and-or graphs (STC-AoG)3 might serve as the forces, fields and particles of cognitive science.

Both predictive processing and STC-AoG converge in that they propose the existence of a mental structure that constantly processes incoming inputs, in other words, top-down deduction addressing bottom-up incoming precepts from the environment. One implication of such structure is that our minds gears our body to be able to perform complex actions and articulate complex language even with small input data, given that as little as there is, it undergoes constant processing from which predictions (stemmed from logical causal relationships established between data) are drawn. Another implication is that the mind discriminates the ubiquitous data in our surroundings, meaning, that we don’t perceive thoroughly the environment, but rather hierarchically choose data that’s beneficial for us to accomplish an immediate task.

If the above similarities hold true, then predictive processing can indeed act as a framework addressing STC-AoG, therefore help explain from the simplest of our daily life activities, while also serve as a framework for studying computational cognitive science.

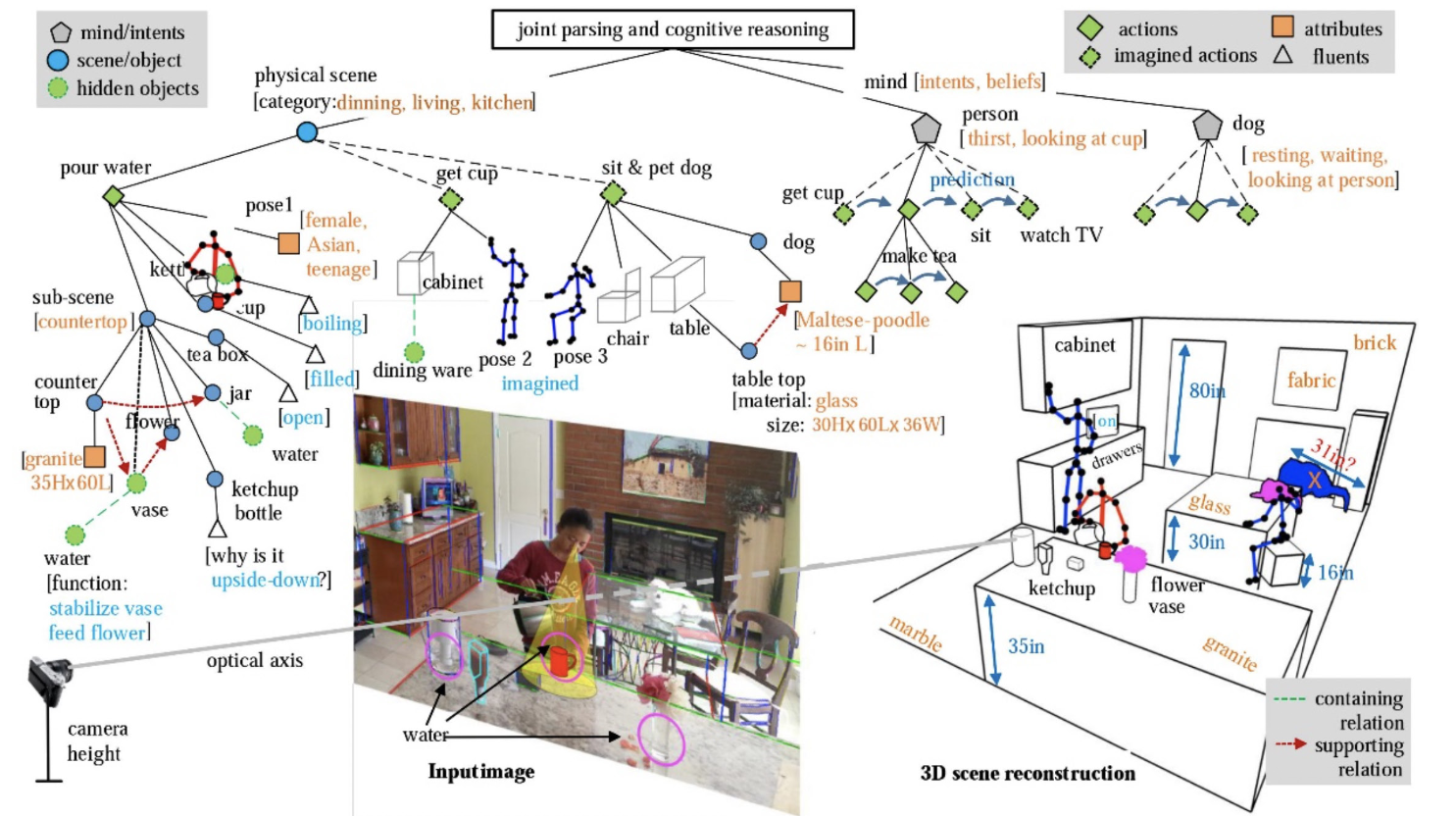

For example, assuming our mind does have a representation of our immediate surrounding that follows a hierarchy and establishes causal relationships in order to make predictions and gear actions, we can then explain the action of drinking water when thirsty. For instance, see Figure 1:

On the origin of such mental representation and how it affects the design of AI

Until now, PP and STC-AoG have been discussed, but why is it that humans were born with such mental structures? A possible answer is given by Prof. Zhu, and is also mentioned by cognitive neuroscientist Anil Seth4, which regards survivability. Perhaps it’s an innate property that humans were born with, but the pursuit of survival can provide an explanation to a lot of fundamental aspects of the mind, such as the origin of PP or the STC-AoG, that is, we have that internal predictive structure so that we can act accordingly to survive in an environment by reducing harm to our body, minimize fatigue, feed ourselves properly, maximize rewards, among others. Survivability also accounts for the origin of communication, given that cooperating with other beings and environment through language was meant to enhance survival.

Another example, now taking survivability into account, would be regarding an individual perceiving a sandstorm incoming; in order to reduce harm to his eyes, his mental structure would parse the elements in his surrounding (clothing, eyeglasses, accessories), predict their functionality and respond to the changing environment by acting (using scarf to cover eyes). Notice that he doesn’t necessarily parse everything in his surrounding, meaning that he might ignore the exact temperature of the environment, sunlight intensity, air speed, whether there’s a tree five miles away from him, among others, hence it’s a discrimination of inputs, but despite hierarchically choosing certain inputs he can still design a series of steps to protect himself. Conversely, we can ask why isn’t his mental structure guiding him to receive and withstand pain. Also notice that in this case, PP is not a registry of data as it would mean that if the individual hasn’t been exposed to the environment, then he wouldn’t know how to act as there is no previous information regarding how to behave during a sandstorm.

On Vision and Natural Language processing

Also, PP and STC-AoG can take into account how human beings can perform complex tasks despite having a relative poor amount of input (this is partly due to the natural biologically limits of the eye5, given that what acutely detects colour and details is in the fovea centralis, which accounts for about 15° out of 200° of range of vision (see

If a human were to grab a can sitting on a table, he wouldn’t place much attention in the walls of the room, as they can be internally predicted, nor even the entire table, but part of it. Instead, he would focus his attention on the can, hence can quickly perform the task. This contrasts with, for instance, how Shakey, the robot6, behaved, given that it had to analyse each and every single piece of input independently (walls, floor, objects), without discriminating data, which then made the task of pushing cubes very slow. In that regard, both PP and STC-AoG focus more on drawing logical connections among data input, so that predictions are made, instead of quantity of data input7.

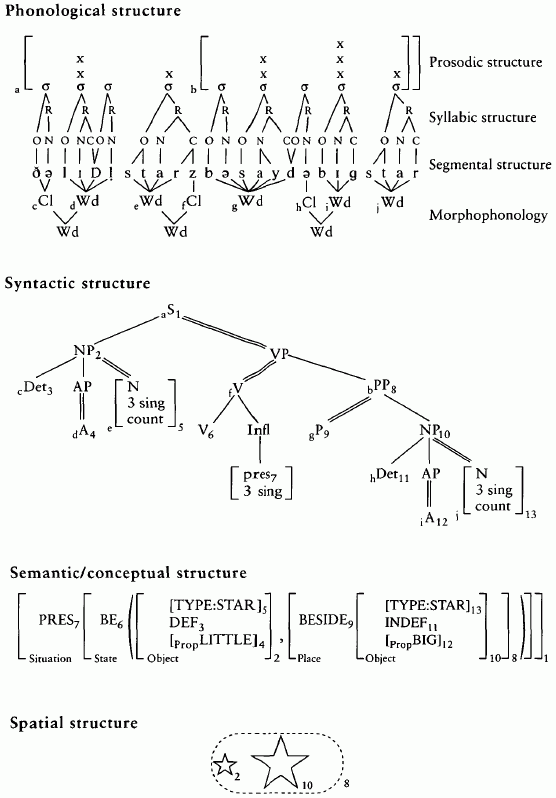

PP and STC-AoG can permeate into the fields of linguistics, mainly because incoming data wouldn’t be treated as unrelated individual chunks of meaningless data, but rather part of a structure that’s constantly discriminating them and drawing connections between them. For instance, regarding the discrimination of data, one can find that sentences can be set into hierarchies as show in Figure 2:

From Figure 2, it’s worth noting that sentences can be broken down into parts that are more important, called the heads of a phrase, and others that are less important, the heads’ complements, hence occupy the bottom of the hierarchy, such as:

In other words, in a verb phrase, we value the verb over everything else, in a noun phrase, we value the noun, so on and so forth. Therefore, in a complete sentence, we would value nouns, verbs and adjectives, but ignore what’s considered complements to those heads. Perhaps that’s the fundamental principle of language, to describe reality by identifying an object (to which we subjectively called a “noun”), that object’s properties (to which we subjectively called an “adjective”), and any object’s function (to which we subjectively called a “verb”). This kind of discriminative parsing of utterances means less amount of data needed to be processed while also maintaining coherent speech:

George: Hi! My name is George

(What Anna’s mind processes: …name … George)

Anna: Hello, greetings from the library located next to Amazon, the best shop ever where you can buy anything you want, at the lowest of the lowest price.

(What George’s mind processes: …library…next Amazon…buy…low price)

George: what was my name again?

Anna: George, by the way, where do I work?

George: At the library, next to Amazon.

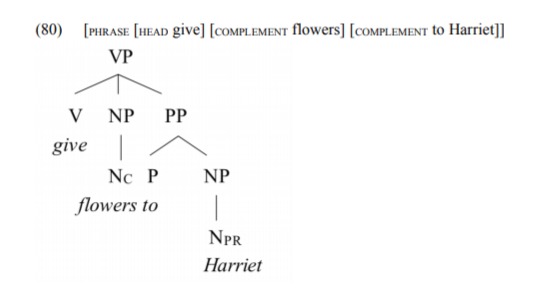

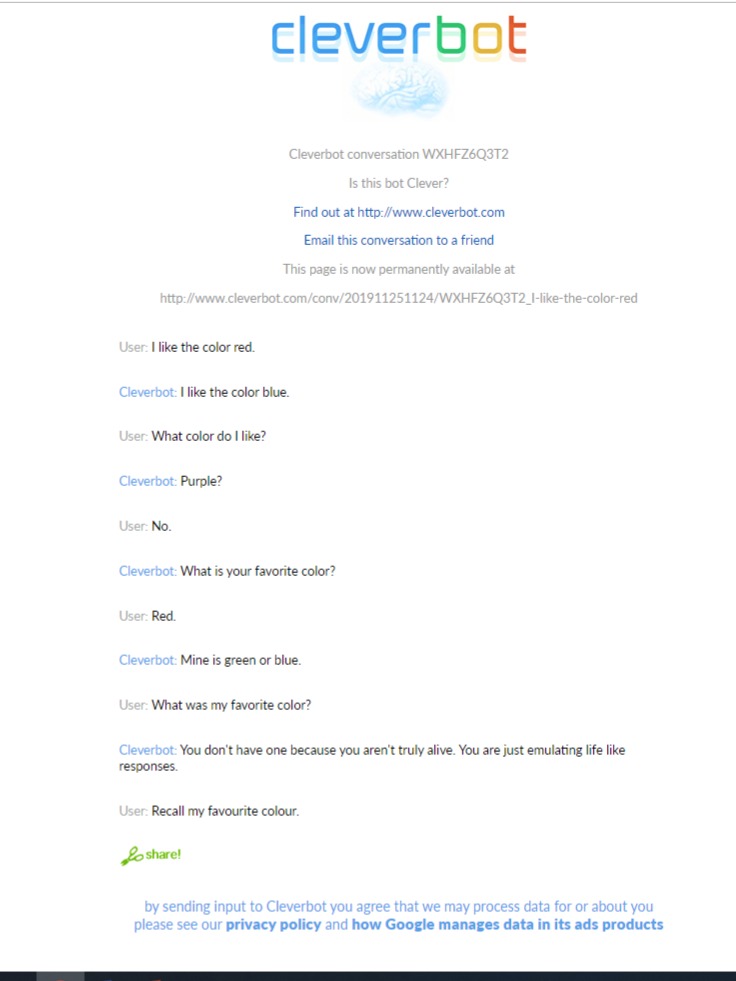

This contrasts with some old language processors given that they analyze data independently, without discriminating nor putting it into hierarchies, which disables coherent speech, and as such understanding, as shown in Figure 3:

Each line of data is treated as a “separate” entity, instead of finding logical connections. Each word of each sentence is also given equal amount of importance.

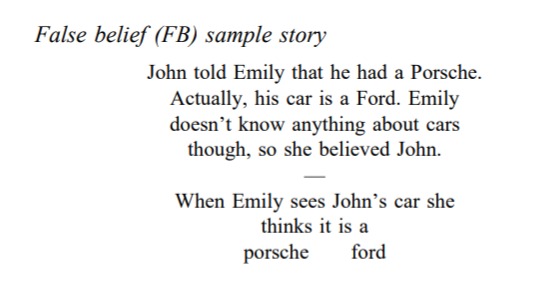

PP also allow us to draw causal relations in sentences and build predictions out of data input. Hence, we can predict what other people might say, and even what they think based on what we have heard about them before or on data previously categorized, see

Nonetheless, given the above example of CleverBot, it would also probably fall short when trying to predict what Emily is thinking.

Therefore, for robots to take the next step of being more human (or the next step for cognitive science), this unifying framework in the form of theory (PP) and practice (STC-AoG) can be implemented.

Alternative to natural language processing

Human language is perhaps designed arbitrarily, therefore it might be too much to program AI so that it discriminates language.

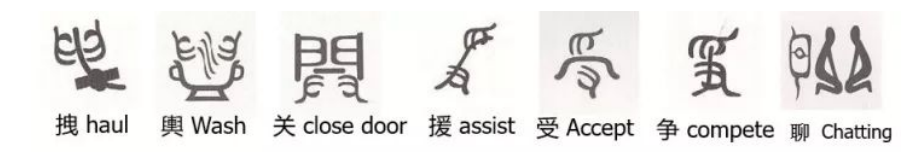

An alternative to that, provided by Prof. Zhu, is to use pictographs, as in Figure 5:

Errata

I wrote this article in 2020, before ChatGPT or any GPT-powered chatbot was released. As such, I have to take back some statements concerning chatbots such as “they’re only able to treat each sentence independently”. Thanks to Transformers, now natural language processing chatbots are able to account for long-range dependencies between the words of a sentence, and thus produce realistic sentences that has long term coherence.

Understanding of the sentences is still debatable. One such test I mentioned previously where we check whether these chatbots are beyond stochastic parrots that predict the next word goes as follows:

You: Do you understand what I say, or are you a stochastic parrot?

Robot: Yes.

You: Please don’t say anything afterwards.

Robot: … (If the chatbot “understood” the sentence, it won’t output words afterwards)

I’m not confident that GPT-powered chatbots are able to carry out instructions, such as stop predicting words (you can try this!).

To see another example where authors exploit ChatGPT being a next-token predictor to gauge its limitations can be seen as follows, with the associated paper:

🤖🧠NEW PAPER🧠🤖

— Tom McCoy (@RTomMcCoy) September 26, 2023

Language models are so broadly useful that it's easy to forget what they are: next-word prediction systems

Remembering this fact reveals surprising behavioral patterns: 🔥Embers of Autoregression🔥 (counterpart to "Sparks of AGI")https://t.co/w0wl4eW1M0

1/8 pic.twitter.com/gTezJKGYA1

-

This is a parallel drawn from UCLA Prof. Song Zhu-Chun’s description of the evolution of Artificial Intelligence research. ↩

-

For empiricism, behaviourism was an example of a discipline stemmed from it. As for nativism, cognitive science emerged. ↩

-

To see further work of Prof. Zhu, please visit VCLA at UCLA ↩

-

He is also a proponent of predictive coding, see

↩ -

This can be evidenced by asking individuals to draw and test whether they can exactly reproduce a landscape. Robots, through cameras, can reproduce exactly the environment, nonetheless, it would ignore the efficiency of inputting what’s necessary while predicting the rest. ↩

-

Robot developed at the SRI International. Performance can be watched at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GmU7SimFkpU ↩

-

Prof. Song refers to “small data for big tasks” as the basis for the future of AI. ↩

-

Briefly, a region in the human temporo-parietal junction (TPJ-M) is involved specifically in reasoning about the contents of another person’s mind ↩