Math, certainty and uncertainty

Two realities: math and nature

I believe there are at least two realities: the abstract, intangible realm of mathematics, which is governed by mathematical axioms, and there exists the real world, governed by laws of biology and physics. These two worlds cannot be disentangled and often overlap: we use math to describe real world phenomena, and hope that physical phenomena respects the constraints modelled by equations described in mathematical symbols.

Math grounded in nature

Given this premise, the following might sound like a boring, repetitive question, but, do you think two plus two equals four in the decimal system?

Exactly four?

This is undeniably true in the realm of mathematics, but I have a lot to say if math were to be instantiated in the real world. This means, when we use numbers to refer real entities. So instead of “two”, let’s think about “two objects”, like “two apples” or “two cars”. Rephrasing the question, this becomes now “do you think two apples plus two apples equate to four apples in the decimal system?”

Though it might sound annoying, I’m not trying to doubt reality.

I’m simply asking, does two, or the concept attributed to the vessel “2”, plus another such vessel abscribed with the concept of “2” equals four?

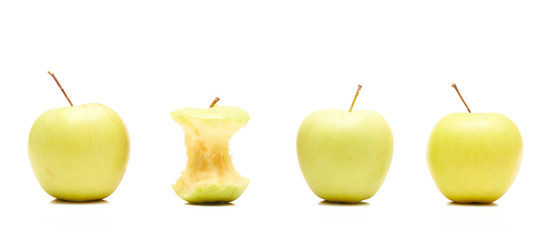

Of course it is, you might say, if I have 2 apples, and a fellow colleague gives me 2 apples, then I have 4 apples Figure 1:

However, if the second apple is bitten, then does that still count as one apple?

Why isn’t it 3.24 apples? They are still apples, bitten or whole.

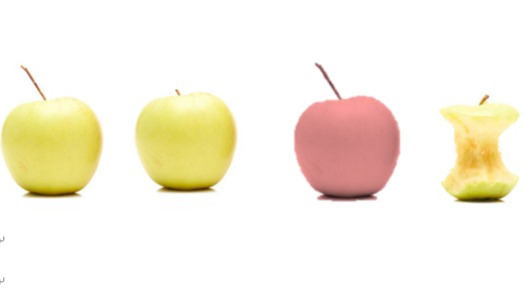

What if the third apple was red and vastly different in size compared to the other 3 (see Figure 2)?

Would that still count as 2 + 2 = 4 apples?

What if the first lost its stem? What if the fourth one had a leaf attached to its stem?

Despite given these hypothetical macroscopic differences, we might still say they are 2 + 2 = 4 apples, however, the concept of 4 apples just became a bit blurry. Does “4 apples” mean that I have 4 identical apples? If I add another fruit, say an orange, then would that make 4 + 1 = 5 apples?

Certainly not, and this is where things get a little bit unnecessarily complicated, but bear with me, I’ve got 2.0 things to say about this.

First, it’s really difficult to define or describe what can live up to the concept of “4 apples”. A bitten apple can count as 1 apple, an apple without a stem may still count as one apple, an apple with other physical properties (different color, no seed, smaller or bigger) can count as one apple, so on and so forth. We can extrapolate a few things regarding this. For instance, that we are rounding up the concept of being apple based on an archetypical apple we have in mind. For example, when we were a kid, we were taught that this fruit with these qualities could be qualified as an apple. This is what’s called prototype theory, which basically advocates that for every concept (say, “apple”, “chair”, “car”) there exists a prototype in our minds that act as a representative of that concept, and small modifications to it doesn’t necessarily change the concept itself. That’s probably why even if a stem falls off, a leaf is missing, or the apple is bitten, they are still considered as “apple”.

However, why are each of the four apples attributed the concept of “1” equally, if they bear some differences towards the “prototype apple” inside our minds (formed during our childhood)? This is where I open a discussion for you to think.

My opinion is that we treat those apples with physical differences equally because we are rounding them up the concept of 1 for each. Returning to the picture, now with the necessary modifications Figure 2:

I believe that I have 3.24 apples, which results from the following sum, respectively: 0.90 apple + 0.85 apple + 0.99 apple + 0.50 apple = 3.24 apples What is 0.90 apple? Based on my “prototype apple”, this concept I acquired during my childhood (you can read Harley’s Psychology of Language for more knowledge), I estimate that the first apple bears 90% resemblance to it, and the same is done to each one of them.

Now, why do I want to share this subtleties?

Well, firstly, I want to share some opinions regarding how we view math. Math is a beautiful myth that lurks in nature, around and inside our mind.

However, I believe that a core principle in math is that when it is grounded in the real world, it loses its exactness. For example, I don’t believe that in any setting, not only talking about apples now, there doesn’t exist an object which deserves the concept of a perfect “1”, nor a perfect “2”, so on and so forth. Then what exists in the real world?

Well, my opinion is that reality is permeated by uncertainty, and any constituent in reality can be represented (and maybe even made up) by approximations only, in other words, instead of saying “1”, we are in reality rounding up “0.999…” or “1/3 * 3”, instead of saying “2”, we are instead saying the rounding up of “2.0000…”.

I think that’s a constituent of reality, and another way to test this is think about measurements. For example, what is the distance between your eye’s retina and the screen? Cells are constantly moving, atoms are constantly vibrating, how can one get a precise measurement then? Actually, one can also say, then, that there exist an infinite distance between you and the screen, why? Because you can half the distance infinite times! I guess that’s a bit far off-topic.

Another little experiment to visualize this continuity of infinitesimals is when you measure your height or weight. You can experience it yourself that there doesn’t exist the perfect measurements, everything is rounded up as there exists uncertainty. Why, then, is this uncertainty ignored when we are counting objects? Discreteness, in this case, is an answer I dispute because, as I’ve shared above, concepts might be revolving around a prototype, therefore the numbers attributed to them might be just the rounding up of decimals; in other words, discreteness is just a cover-up for continuity.

Why is this important?

Implication in science

We can extract the ideas from above and apply them on the field of sciences.

Science can be defined as the systematic study of ourselves and our environment. Systematic in the sense that we follow strict procedures in order to be able to gather relevant evidence to prove or refute a hypothesis concerning nature.

However, I hope I’ve convinced you that uncertainty underlies in math, and similarly, it’s probably a principle underlying the fabrics of the natural world; one could say (elegantly) that science, to some extent, is the “art of reducing uncertainty”.

This is because, even though we follow the scientific method to study everything from the tiniest subatomic particles to the biggest galaxies, we’ve got to take into account that the axioms and instruments we use for measurements are de facto uncertain, and this is without ignoring that due to particles being infinitely big or small, interactions between them might be a story to be explored that’ll never meet its ending. For example, in our biology textbooks we may have learned about the dynamics of several molecular pathways, such as for instance the biogenesis of miRNA or gene translation; however, can we be sure that we’ve understood thoroughly all the proteins participating in the pathway, exactly which genes are the ones transcribed and translated, so on and so forth? Something similar happens when we study biological neural networks in the brain, which in simple terms, is an organ for which we don’t fully understand how it works because it’s permeated by complexities, uncertainties we can’t easily sort out.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that we should feel “demoralized” by these infinitesimal complexities lurking in the fabrics of nature, as well as in the techniques and instruments used to measure that reality; quiet the contrary, we should embrace these uncertainties and, through the power of science (the art of reducing them), try to minimize them as possible for the benefit of discovering the unknown, unraveling the mysteries behind nature and innovate for the benefit of everyone. So, in short, in the field of medicine for example, even if drugs intended to target specific enzymes or receptors don’t work as intended because perhaps we may have misunderstood certain pathway or molecule-molecule interaction resulting in unintended toxicities, we shouldn’t be discouraged as that uncertainty in understanding is a principle of nature we can combat with the power of science.

In a more common scenario, whenever we are reading a textbook or book explaining certain subject, we should bear in mind that there doesn’t exist the perfect description or definition for any concept in this uncertain world, and be prepared to always learn more by asking:

- Why is this concept stated like this?

- Is this idea thoroughly explained?

Among others.

In the end, embracing uncertainty allow us to be humble and always be curious for more understanding. Always explore, and inquiry further through the uncertainty and beyond so that we can admit that what we currently know may only be what looks like the whole story, when in reality is just a chapter… across all the fields of science.

PS: Further reading I recommend is https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(10)60719-2/fulltext

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: